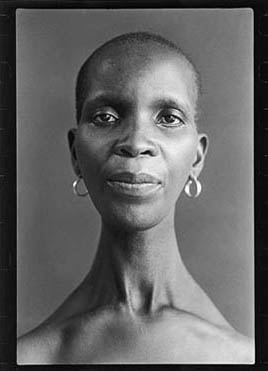

The physician, Miguel Ribeiro, has dared to find beauty where other practitioners have been concerned only to objectify the subjects of their clinical and forensic studies, and where ordinary folk are wont to avert their eyes from fear or even disgust.

He has done this without fudging but indeed by precisely applying the understanding afforded him by his profession.Nor has he falsely dramatised or indulged in sentimentality. In the result he has produced photographs of pathologies of the human condition which are remarkable for the depth of the paradoxes they pose.Somehow the scientific is not obscured by or sacrificed to the aesthetic, yet the clarity of both, seemingly, is heightened.And far from beauty concealing or minimising what is suffered, it seems to make the condition suffered both real and immediate.Science and art, the beautiful and the terrible are here brought into rare and moving contiguity

David Goldblatt

When the body, or a suggestion of it, is mentioned in art or in daily life (in fact the two are often separated by intangible barriers), we think of a universe stirring within the borders and the ways of eroticism.

The stereotyping of that reference to the erotic also poisons the very way we look at the body and how we appreciate it in terms of the ideology of "eternal youth" and other commonplaces. There is even an erotic neolanguage with its own grammar and lexicon, where nothing has any meaning whatsoever and where the pieces might be arranged in any possible way without altering their significances - these become sentences repeated ad nauseam, in endless speeches about "staging", "mutilation", "pleasure", "the ephemeral". The body is transformed into geography and scenery - but ceases to be a body. It becomes a mere role, a circumstance. On the contrary, in these photographs of Miguel Ribeiro the body, beyond its ability to communicate with reality, is a true ghost – an obsession, a fragment, suspended and lethal material. One additional gesture and it would all collapse: the composition (balance, light, reflection, geometry), the effect (panic, surprise, commotion, irreverence), the intention. The truth that eludes us or that we never succeed to formulate. Was our body able to do this? Is this gesture ours? This landscape, where did it come from? These uncertainties permeate his photographs. They are our wonder seen from another side, from another perspective that only seldom reveals itself. This medical look is unexpected and may be frightening. Bur, lost in contemplation, we forget it is around us, walks with us, and that we are nothing but examples, not always glamorous and triumphant./p>

Francisco Jose Viegas

Casa Fernando Pessoa, Director

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

|

This body is whatever we wish to see in it. It can be a landscape. It can be an object, a building. It can be the moonlit desert. A ship’s rigging. A triumphant arch. It can be a square, a circle, a straight line.

In certain photographs by Miguel Ribeiro I see time. Not the passing of time, but the time needed to dig furrows, tracks, ruts and wrinkles. In certain phases of the body, the body itself is invisible. What remains is only a hint of an idea, which keeps forming and fading in one’s head until fixing upon a recognizable physical entity.

Some would call this abstraction, but abstraction which carries no trace of an idea or doubt is not abstraction, it is emptiness. And man, like nature, is terrified of emptiness. Miguel Ribeiro began the work of these representations many years ago, in an obsessive and primordial way, as if there were no other reason for living but to photograph a specific intimate life of the body in fact, his own — for being the one most at hand, which he could call upon, display, and intimately invade without danger of rejection or exhaustion. A body which would accept being worked over by light and shade, by speech and silence, until expressing every possible conjugation of the verb “transform.” Because the subject of this photography is also transformation; the transformation of the visible and the invisible, which is to say, God’s work.

Skin-dunes and finger-valleys, mouth- and eye-caves; here a forehead crumpled like worn cloth, there the creases and cracks of bare skin; or thick knots, as if an inside-out body were being exposed: distilling the image over and over again until resolving the problem of bodily motion, which is the natural tendency to cover up or fool our fear of repose. For the body, immobility — not a mere pause in movement, but the total absence of movement — is the moment of death, the moment preceding decomposition. The moment when the body still “lives” before its extinction. The moment of absolute finiteness and all termination of strength.

To fleetingly capture this absence of dynamism in a living body is to force the body against nature, to consign it to an instant of absolute solitude. The photography of Miguel Ribeiro immerses itself in these contradictions, which, being a physician is not surprising; as a physician he has with the body —including his own body — an abstract relationship. He uses abstraction as a clinical phase of the evaluation process, as an exercise which is represented abstractly through symbols, words, numbers, or notes more easily than by concrete and tangible means. To write the algorithm or the musical score of the body, to decipher the algebraic equation, establish the grammatical norm, or the applicable trigonometry is something that an artist, however, can do more easily when he is not obliged to use the body as practical or scientific subject matter.

The task: to plasticize the body, sculpt and aestheticize it until finally renouncing the desire to find in it any signs whatsoever of its decrepitude or youth, beauty or health, or its immediate integration in a recognizable, human whole.

Which is not to say that the physician does not come to the aid of the artist, using his body-wisdom to aid his art, even as art has a wider scope than medicine. In medicine, the body is precisely this: the extent of its breakdown into material components. In art, a body can be everything: its progressive spiritual deconstruction into angles and peaks, planes and counter-planes. An analytical geometry achieved by the lens and the eye, machine and thought.

It is as if this photography were telling us that a body can be whatever we wish to make of it. It can contain a sermon. A hair can hide a glacier, skin can flow into an abyss, a mouth can silence a scream. A beard can be the beginning of a thorny path, and the gentle curve of a membrane an eclipsed moon. And through this multiple body we navigate, with our compass and astrolabe, that is, with our intelligence and senses.

This is a group of photographs of my body taken between the years 2001 and 2008, the period I was involved with this subject. I bought my first camera in 1978, and from the very beginning would occasionally incorporate a hand or other body part in photos of landscapes.

Yet it was only in 1985, while living in South Africa (1980-91), that I first used my body as the central subject of photographs in a systematic way. The appeal of this theme, however, lasted no longer than eight or nine months, overshadowed by passion at the time for medical photography.

In December 2000, again in South Africa for New Year's eve in Cape Town, my interest in self-portraiture was revived, now lastingly and as the central theme in my photography. Until mid-2003 the selected body area was typically photographed in interaction with objects or landscapes. Thereafter I returned to the neutral backgrounds of 1985, and came closer to the more intimate spirit of that period. In general I sought to isolate a body part, strip it of its bodily identity, and make it function as an autonomous subject to be explored, in a more or less abstract way, as an object with a texture or with sculptural potential.

The first photographic series date from mid-2004. In late 2005 and throughout 2006 I strived to assemble photographs into composite pictures with a dual reading, of the whole and of the individual images. In 2007 I began converting images from analogue to digital, and, taking advantage of the temporal conception of the series, I started sequencing the photographs into short films with music. Such medium proved to be the most adequate vehicle for some of my series, while ideally conveying the obsessive nature of the work.

The body, given its formidable expressive power and unending versatility, is an inexhaustible and deeply engaging subject. And when we use our own body, it is capable of responding instantaneously and with minute accuracy to the ever-changing action/reaction that modulates the flow of conception, without the losses in transmission inherent in the use of a model.

I have seen sadness in my face

and unwillingly seized the feel of it:

a slight pressure and heaviness, a vague wrinkling sensation, an uneven tightness...

All of a sudden a wink, or nothing, wakens me to the awareness of disquietude in my still face –

and that transient map of faint ill-defined perceptions

abruptly and sharply draws the jagged portrait I have seen,

and I know I am feeling sadness in my face,

and I feel sad..